Modern and contemporary painting all too often seems like a solution in search of a problem. The contemporary painter is obliged to qualify and explain his work in terms of some unique, personal vision or concept; art exhibitions today involve as much reading as looking. But it wasn’t always this way: in the past, artists were patronised and commissioned to produce great art; art was a business and the client supplied the artist not only with remuneration but also with purpose. By today’s standards, the range of subject matter was narrow and predictable; religious, historical and mythological themes dominated. But the artist had the benefit of a brief – and probably in many cases a detailed one. The question of what to paint – or even why to paint at all – wasn’t a source of concern for the artist; all he had to do was to decide how to paint. Unlike the contemporary artist’s open-ended, high-minded (and sometimes desperate) search for originality and authenticity in his work, the Renaissance painter’s challenge was confined to one of design: finding a way to satisfy the patron’s requirements and his own artistic preferences at the same time.

You could argue that the artist of the Renaissance had more in common with the contemporary illustrator than the contemporary fine artist not only in working to a brief but also in observing traditional techniques and craftsmanship. Having a purpose, being able to establish clear objectives, makes a difference.

One under-appreciated form of art-with-a-purpose is the cartoon.

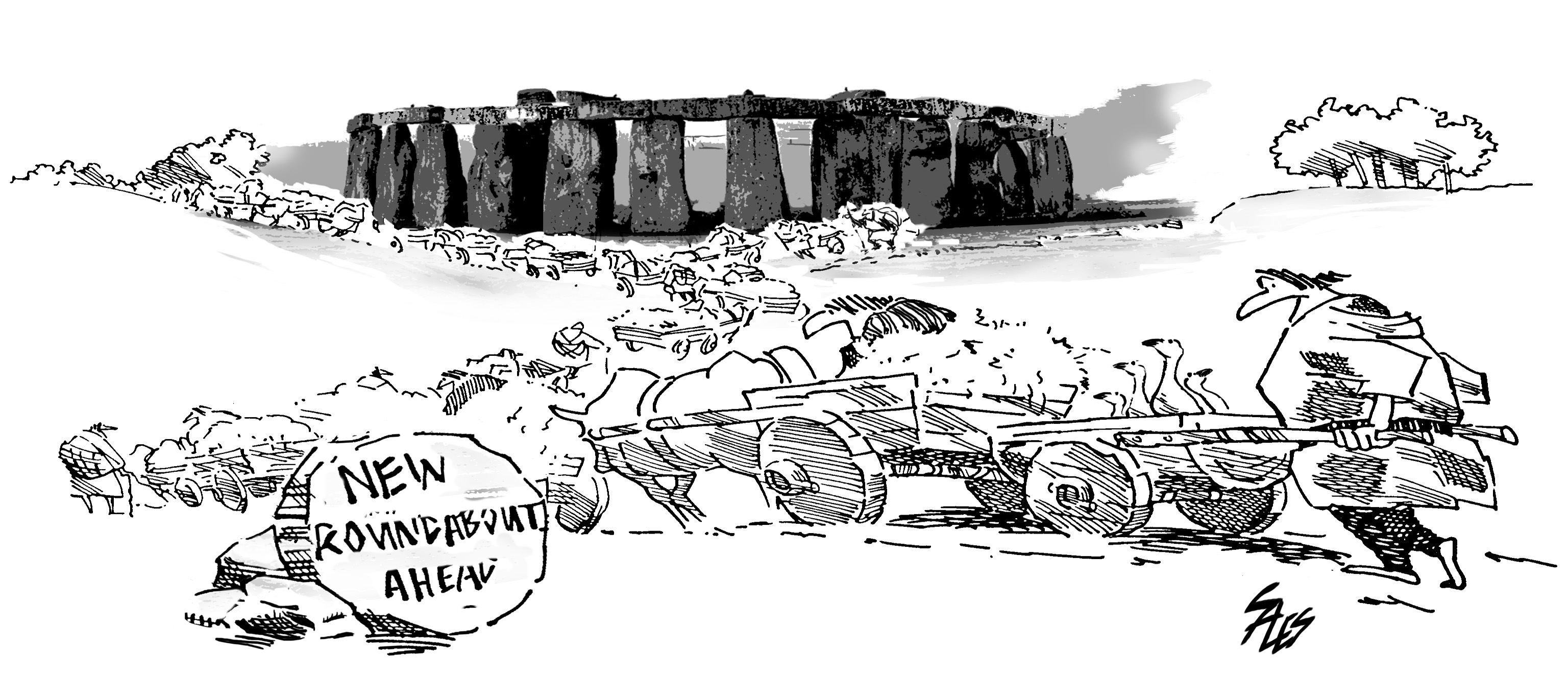

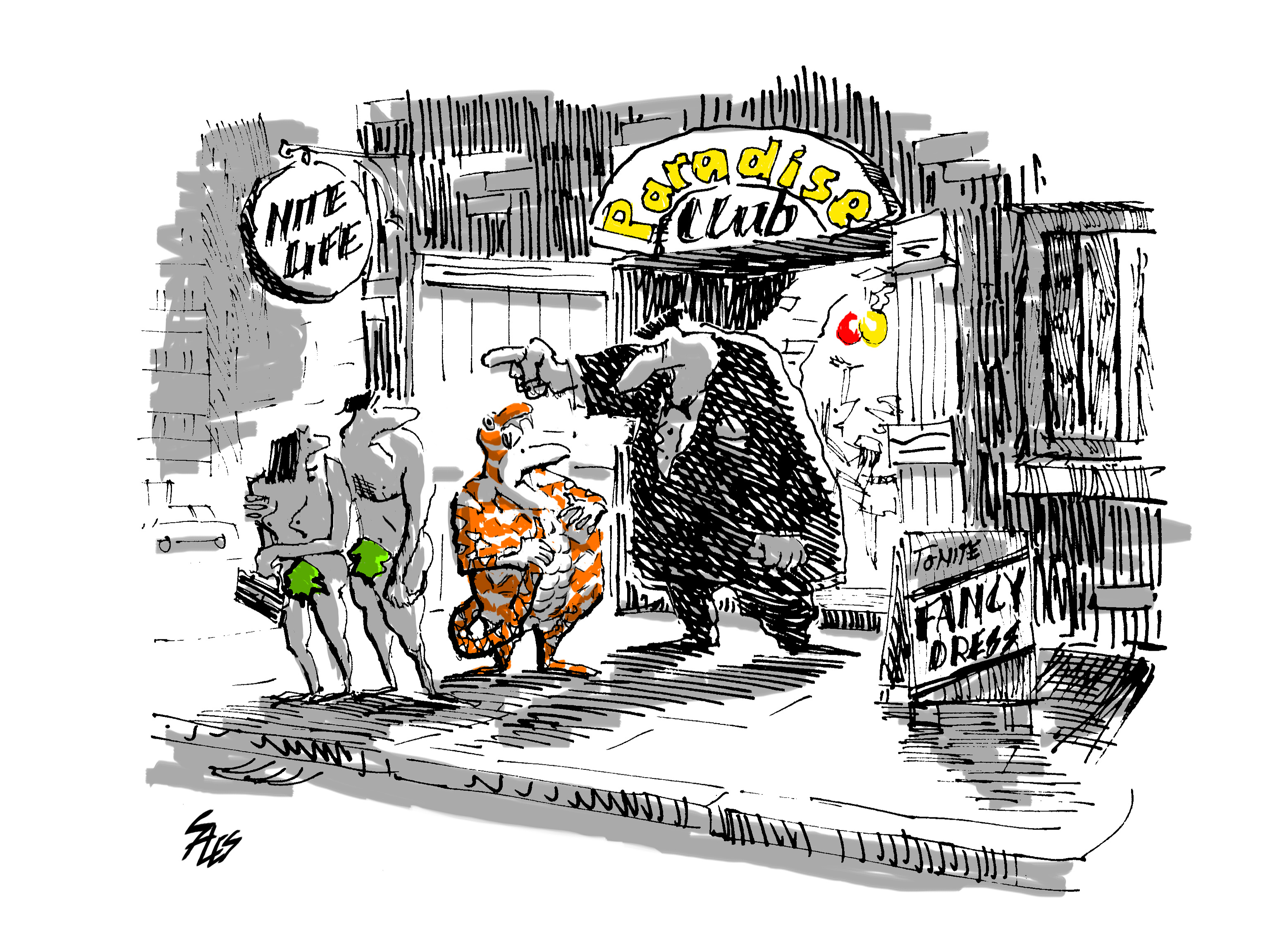

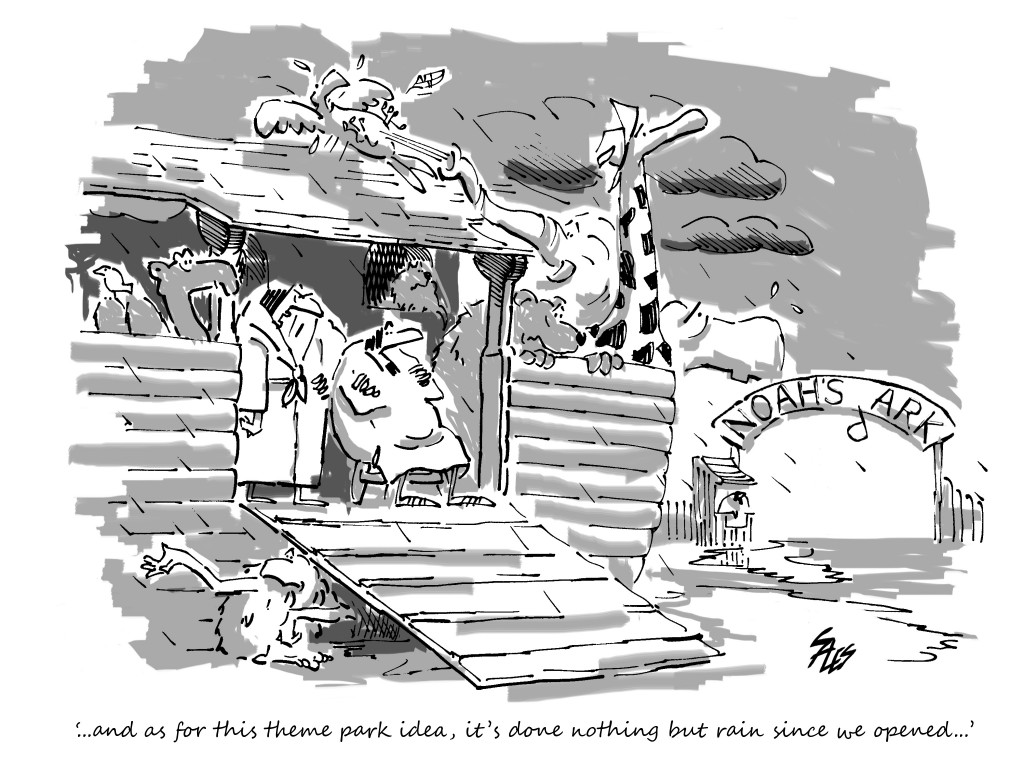

No, not the elaborate line and colour studies of the old masters, but those little single panel humorous drawings that you find in periodicals and newspapers. Here in the UK, during the 1960s, cartoons were a feature of many publications, including Punch and Private Eye; one of my favourite sources was a weekly paper called Weekend which often included the work of an excellent cartoonist, Mike Williams. Sadly, cartoons are much less in evidence in the popular press than they used to be. (The cartoon gallery includes some of my own efforts.)

Perhaps it’s because the purpose of the cartoon is to make us laugh that it’s rarely taken seriously as an art form. Yet, in the best cartoons, the drawing straddles the divide between illustration and fine art, while in the worst it’s simply redundant, contributing little or nothing to the idea; the humour is confined to the caption – and the caption is essentially a ‘one liner’ gag which doesn’t need the embellishment of a drawing at all. In the ideal cartoon, it’s the caption that is redundant and the drawing that expresses the whole idea – much like contemporary and modern art.

How does the cartoon work? Where does the humour come from?

I like to think of the caption and drawing as a sort of comedy double act. Here are a couple of examples.

The humour arises out of the incongruity of caption and drawing; separately, each may be quite ‘sensible’, logically consistent and unfunny. Put them together, however, and sparks fly; absurdity trumps expectation, and the result is humour.

The primary role of the drawing in a cartoon is to provide a context, a background against which the caption is interpreted. The drawing will normally be perceived before the caption, partly because we take in images at a glance, all at once, and partly because the drawing is physically larger than the caption and so commands attention. A caption, on the other hand, has to be read – and reading (especially if the caption is lengthy) is a much slower process.

The best cartoonists are fine draughtsmen and the best cartoons show all of the qualities you would expect in a fine drawing: economy and variety of line, effective composition, and above all a distillation of subject matter to its bare essentials.

In some ways, cartooning is to drawing what jazz is to music: both require the talent and skill to improvise and the ability to express something in a unique and personal style and both have their favourite repertoire of motifs – for the cartoonist they include desert islands, dungeons and dragons (usually in the form of domineering wives). A popular cartoonist’s style is immediately recognisable: think of Giles or one of the political cartoonists such as Scarfe or Steadman. Being able to draw the human figure convincingly, to capture a facial expression or a posture and still make it a minimal and personal statement is much harder than it looks. Just because cartoon figures are usually exaggerated, distorted and simplified doesn’t mean that they lack artistry or anatomical authenticity. The accomplished cartoonist can convey energy and apathy, euphoria and despondency, aggression and submission with a few brisk strokes of the pen – and still make the work identifiable as his own.

One of the challenges and frustrations of constructing a compositional study for a painting is resolving the drawing. Resolution means working out every part of the composition explicitly so that when you attempt the painting you aren’t faced with the uncertainty of inventing or fudging some parts of it. A fully resolved drawing is theoretically reproducible; that is, because every line has been considered and defined, the whole drawing could be reconstructed without reference to the original. Of course, in practice, most compositional studies will be too complex to fully resolve and reconstruction without the original as reference would be impossible. The cartoon drawing, however, can be different.

To the practised cartoonist, particularly the strip cartoonist, depicting his subject matter becomes as familiar as writing. As he draws, he constructs his characters with the same certainty and facility as he constructs the letters of the alphabet as he writes. It is quite possible for him to fully resolve his drawing; after he has finished it he could tear it up and produce a near identical copy without reference.

This idea of resolution and reproducibility may seem abstruse, but I believe it’s a key aspect of the picture-making process because it means that if each step in the process is resolved then it puts the whole work on a solid foundation.

Incidentally, it is possible to achieve resolution of more complex, naturalistic subject matter. The figure, for example, can be constructed from a series of geometric solids: Bridgman’s anatomical drawings use this approach. Using spheres and cubes and the like does make it possible to predict or plot the position of every significant point in the composition. Although the method differs from that of the cartoonist, the outcome is much the same.

One final point. A credible scientific theory must be testable, otherwise it can neither be proved nor disproved. In fine art, however, there is no test of the ‘truth’ of an artist’s creation – unless, that is, you believe in the infallible taste (and usually unreasoned judgements) of the art critics. But there is always one indisputable test of the validity of the humble cartoon: if it makes you laugh, it’s good.