[This post supplements three videos on watercolour emulation with the Infinite Painter app. If you prefer watching to reading, you can find the videos here.]

Digital Painting: The Positives

If you’ve tried your hand at painting with traditional media such as oil or watercolour, you’ve probably been irritated and frustrated at times by the sheer messiness and imprecision of it all. You find yourself surrounded by smelly rags (oil), soggy tissues (watercolour) or clouds of pigment dust (pastel) as you try to fathom the vagaries of colour-mixing, tone control and technique (especially watercolour technique). Wouldn’t it be nice to work in a medium that lets you focus on the essentials of painting and minimises the distractions of equipment and technique – a medium that’s completely clutter-free and that lets you control all your materials with mathematical precision? If that sounds appealing, then you might enjoy exploring the world of digital painting, the ideal medium for artists who are control freaks. Apart from providing you with a tidier, healthier working environment, digital painting offers some real benefits to anyone who wants to improve their art.

For example, working with packages such as Adobe Photoshop or Corel Painter allows you to endlessly re-work a painting without losing the original state. Speculative brushwork that turns out to be a faux pas is easily remedied with the Undo button. If you want to try out more radical changes, you can apply them to a separate layer or layers which are superimposed (blended) with the underlying painting. If you don’t like the result, simply delete or turn off the layer(s) to restore the original. Layers can also be used to create subtle changes such as applying a delicate glaze over part or all of the painting to adjust the tonality or colour balance.

Being able to make changes (even wholesale changes) to a work without having to commit to them is a big advantage of digital painting making it an excellent (and much less stressful) way to experiment with pictorial composition in particular.

Colour, too, is an area where digital painting comes into its own. The colour picker lets you choose the exact tint or shade of a colour or you can select a colour from a reference image using the eyedropper tool. You can even set up your own personal palette of colour swatches so that you always have the precise colour you need at hand (very useful for flesh tints, for example, in portrait work). If you are really fussy, colour can be specified numerically by choosing exact values for the red, green and blue constituents of a mixture.

Watercolour Emulation

But what makes paint packages like Adobe Photoshop and Corel Painter really appealing to artists is their capacity to emulate traditional media such as oil and watercolour. Over the years, the developers have improved and extended these emulation features to the point where they can produce very convincing results. Let’s have a look at some of these features.

Both Photoshop and Painter have a comprehensive set of brush presets – ready-made brushes with specific properties; so you might have a brush that emulates a dry brush stroke or one that produces a wet-in-wet effect. You can also create your own brushes by selecting from a range of brush tips and customising the associated controls such as flow, opacity, jitter and a host of others (no need to go into them here). It’s even possible to set the properties of the virtual watercolour paper. (Any experienced watercolourist knows how important it is to choose the right paper.) The range of options with Corel Painter, for example, are pretty amazing: apart from changing paper texture you can control properties like paper absorbency, drying rate, wetness and even how the paint behaves as it dries (granulation, edge effects).

I’ve spent many hours experimenting with brushes and paper in both Photoshop and Painter. Understanding the full range of possibilities is quite a challenge. It pays to be methodical: explore each control thoroughly trying different settings and making notes as you go. If you can’t find (or create) the brush you need, there are plenty of online sites offering custom brush sets for download – often for free. There are also lots of tutorial sites and forums offering advice if you need it.

Digital Painting: The Negatives

So far, then, it’s all positives with digital painting. The tools we need for watercolour emulation exist; we just have to switch on our computers/tablets and start painting. Which is what I’ve been doing on and off over the past four years, and while it’s been very interesting – fascinating even – to work with Photoshop and Painter, I have to point out that there are pitfalls. Because of the complexity of digital paint programs and the wealth of information out there, it’s easy to slip into ‘Google mode’ and spend too much time searching online for answers instead of taking a step back and thinking carefully about exactly what you need to satisfy your idea of a convincing digital watercolour.

If you look online at tutorial sites or forums/communities on digital watercolour painting, the usual approach to emulation is by amassing collections of custom brushes, the idea being that you have a dedicated brush to create each watercolour effect. So you might have a ‘dry brush’ brush, a ‘wet-in-wet’ brush or a ‘hard-edged wash’ brush. This is fine if you end up with a (small) handful of brushes with which you can become familiar and which have a degree of versatility like, for example, a real No.6 round sable which you could use to paint a broad wash or exploit its fine point to draw a delicate line. But this is not what happens. Because most users don’t know enough about the brush controls, they accumulate what are in effect duplicates that differ in some easily-adjusted parameter such as brush size or opacity (opacity equates to colour intensity in the real world). The result is an unmanageable number of brushes to work with. Worse still, a lot of watercolour brush collections include brushes that produce high level, shortcut effects. So you get brushes that paint grass or leaves or clouds. Even brushes that can simulate genuine watercolour effects such as wet-in-wet are often over the top: they may be all right for ‘rain-curtain’ skies but are usually too heavy-handed and uncontrollable for much else.

You can’t paint fluently if you have to figure out constantly which brush you need to capture a particular effect and then trawl through a lengthy collection to find it. We need a different perspective on the problem.

Instead of adopting an effects-driven approach to watercolour emulation, my suggestion is to focus on watercolour technique. What this implies is that the experience of painting a digital watercolour should be as close as possible to the experience of painting with real materials (without the mess of course).

But how do you do it? The process should be simple enough: first, identify the characteristics of the watercolour medium that you consider important; second, choose or create a minimum number of brushes to capture those effects.

Effects to emulate

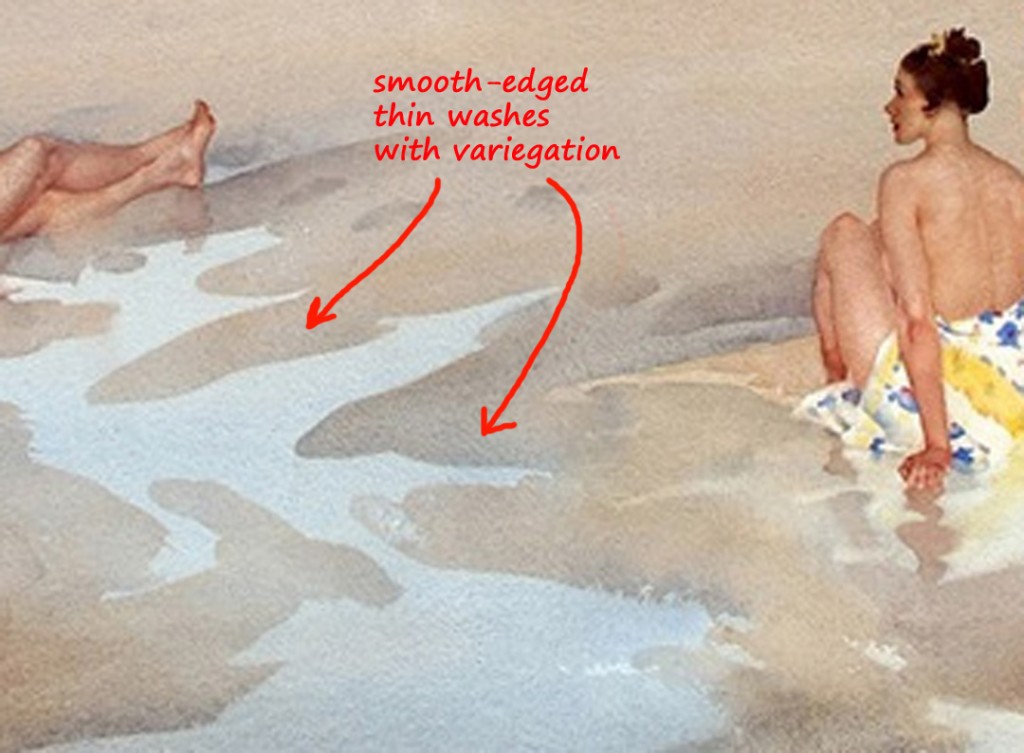

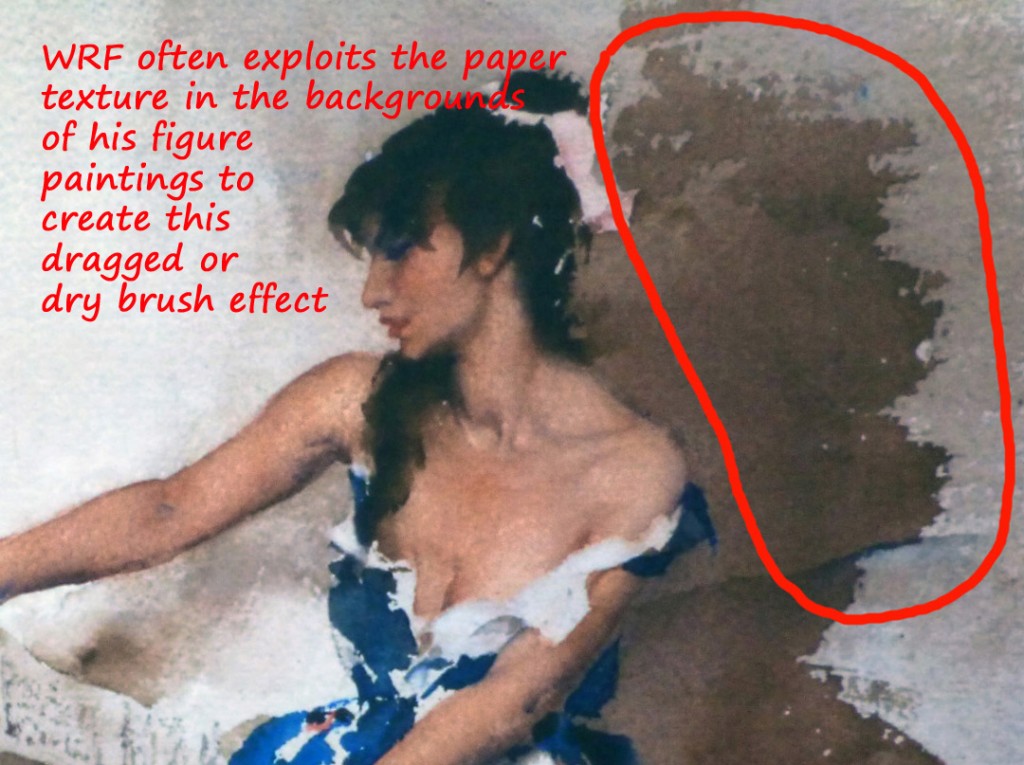

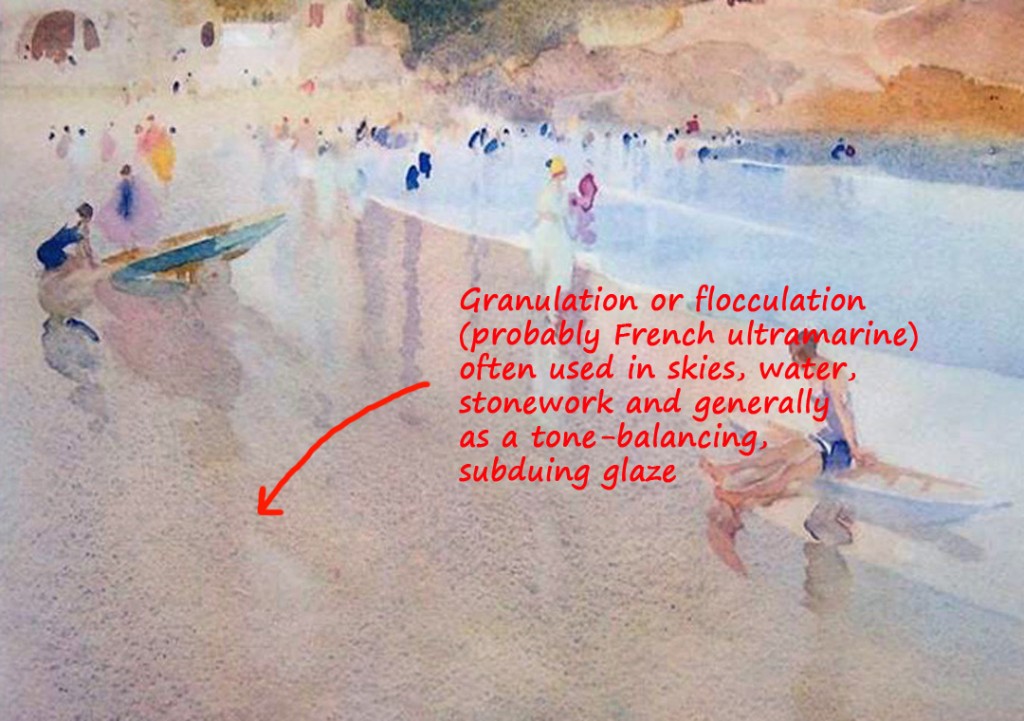

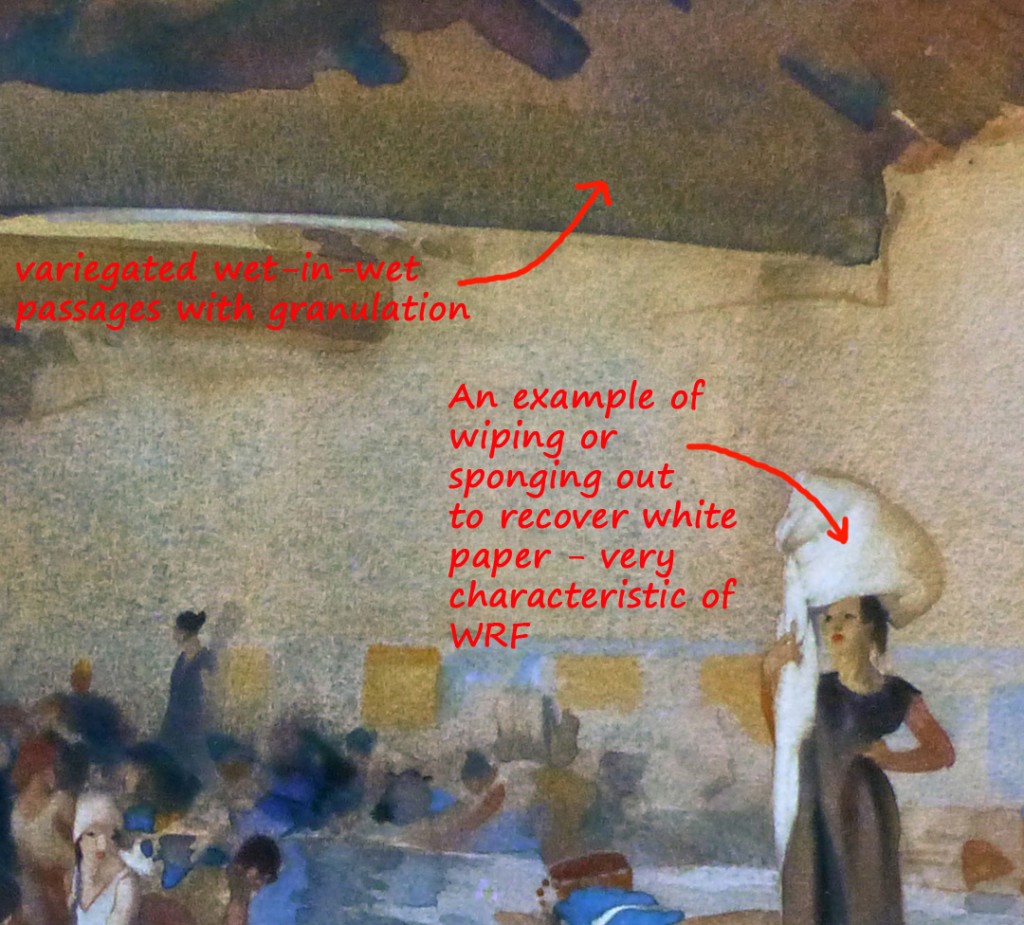

In order to identify the effects to emulate I’m going to use the paintings of Sir William Russell Flint as a source and benchmark. Why WRF? Flint’s mastery of watercolour technique is generally acknowledged. He could capture the texture of stone, timber, water, foliage, flesh and drapery with equal facility. He was also a very capable draughtsman. Flint stressed that he knew no ‘tricks’ with watercolour other than control of the medium. I’ve chosen a number of effects that he often used in his paintings. Here they are:

The interesting thing about Flint’s watercolour technique is that despite the remarkable control and inventiveness that it shows, he never lets the medium dominate the subject matter. He doesn’t let pure watercolour effects take centre stage: there is a subtlety and restraint in the way he exploits the medium and bends it to the purposes of representational art. His paintings may have that fresh look about them that watercolourists cherish but Flint was no purist: he reworked his paintings constantly, washing out and repainting passages, using Chinese white where he couldn’t recover the natural white of the paper. But in keeping with the way he handled paint, Flint was judicious in the use of technical ‘tricks’. He might use body colour white to refresh the paper surface but he didn’t resort to opaque watercolour to pick out highlights or generally ‘energise’ an overworked painting. Likewise, you won’t find him throwing salt or flicking paint at a picture simply to manufacture an ‘interesting’ effect.

The Paint Program

The software that I’ve chosen for watercolour emulation isn’t a full-featured Windows or Mac application like Photoshop or Painter; it’s a relatively modest Android app called Infinite Painter created by Sean Brakefield. I’m using it on a Lenovo A2 A10-70 tablet. The three videos accompanying this post include five demonstration paintings of details from Flint watercolours. Also included are the settings for each of the brushes used.

Although the videos describe four brushes, the five demonstrations were done almost exclusively with just one which I’ve labelled Wet-In-Wet. The same brush was used as a blender and eraser. (The blender allows you to move and shape painted passages – very useful for detail work especially on the figure.) Miraculously, it is possible with just this one brush to capture most of the watercolour effects shown above. You can recreate those rich blended darks; the textured, variegated washes; even fine rigger-like details. I’ve shown in the videos how it can be used to paint skies, water, architecture and figures. The other brushes are:

- Dragged Stroke which emulates the dry or dragged brush effect in the backgrounds of many of Flint’s figure paintings (used in only one demonstration painting)

- Graduated Wash which is self-explanatory (this brush was not used at all in the demonstration paintings)

- Glaze which gives a sharp-edged flat wash (used with the Wet-In-Wet brush to create variegated effects)

I did use a fifth brush called Granulation in one painting to try to capture the grainy quality of many of Flint’s washes (probably achieved by applying thin washes of French ultramarine; the wetter the application, the more pronounced the granulation or flocculation).

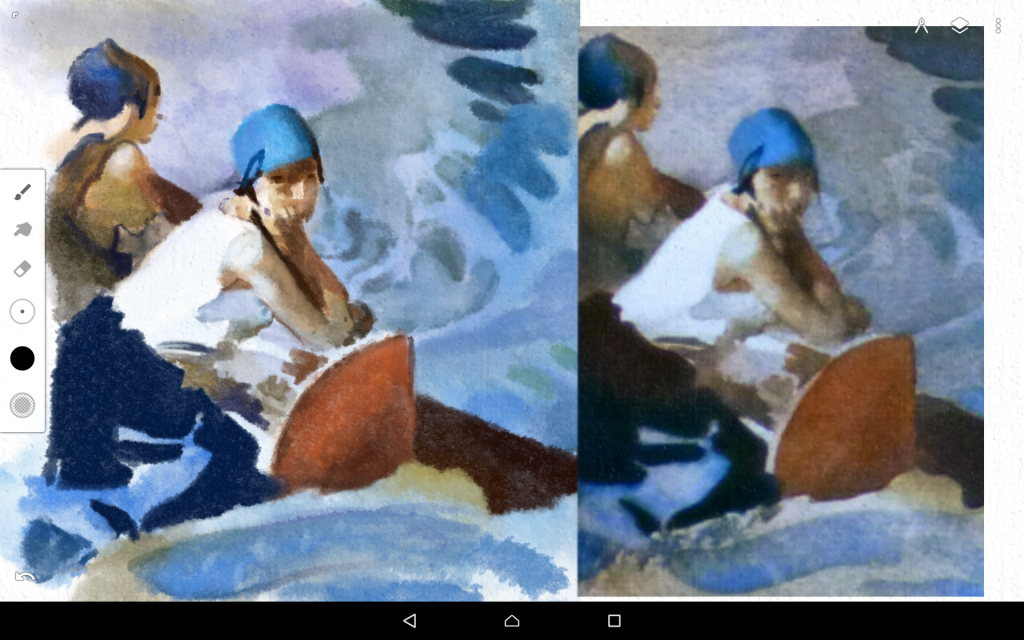

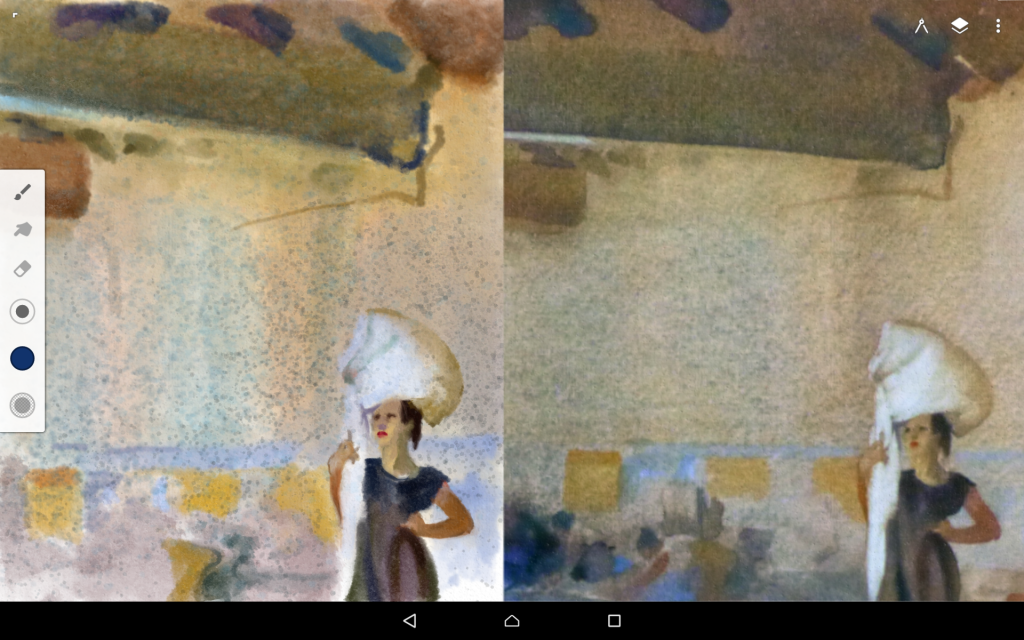

Here are some screenshots from the demonstration paintings:

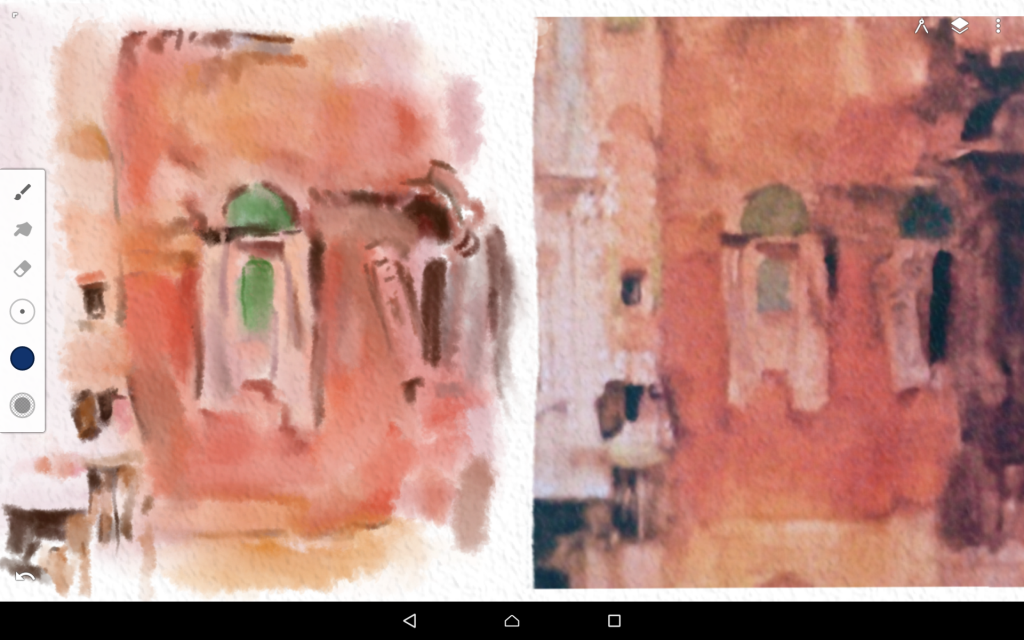

The copy is on the left. It’s taken from ‘The Great Lavoir, Antibes’, as is the next screenshot. Again, the copy is on the left. This is the painting which uses the Granulation brush for the speckled background effect. This brush was used on a separate layer just like a real glaze wash.

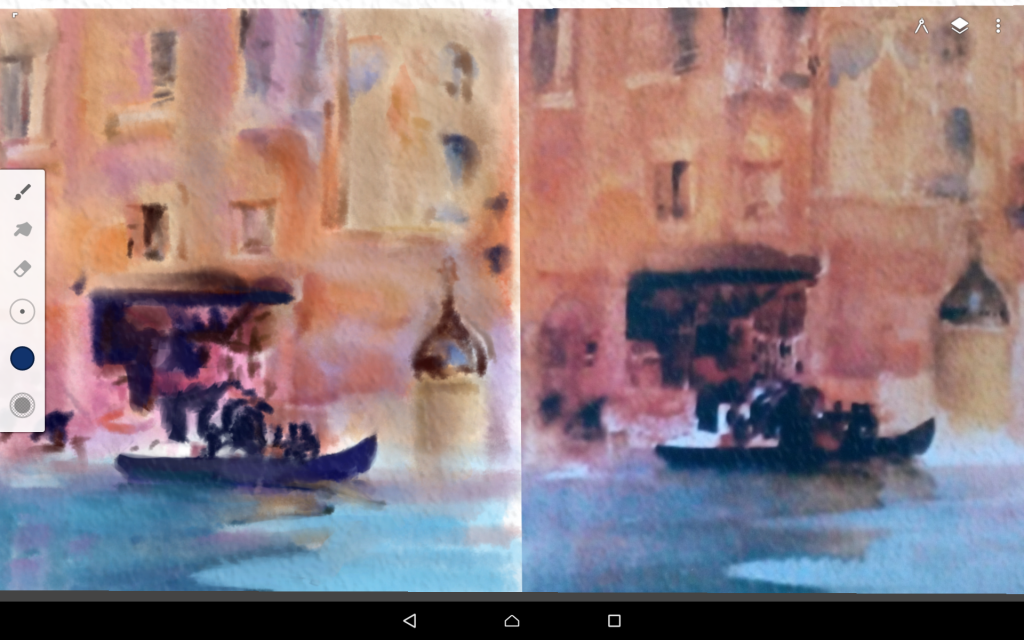

This image is a detail from ‘Palazzo On The Grand Canal, Venice’. Copy on left. The whole painting was done with the Wet-In-Wet brush.

This is another detail from the same painting.

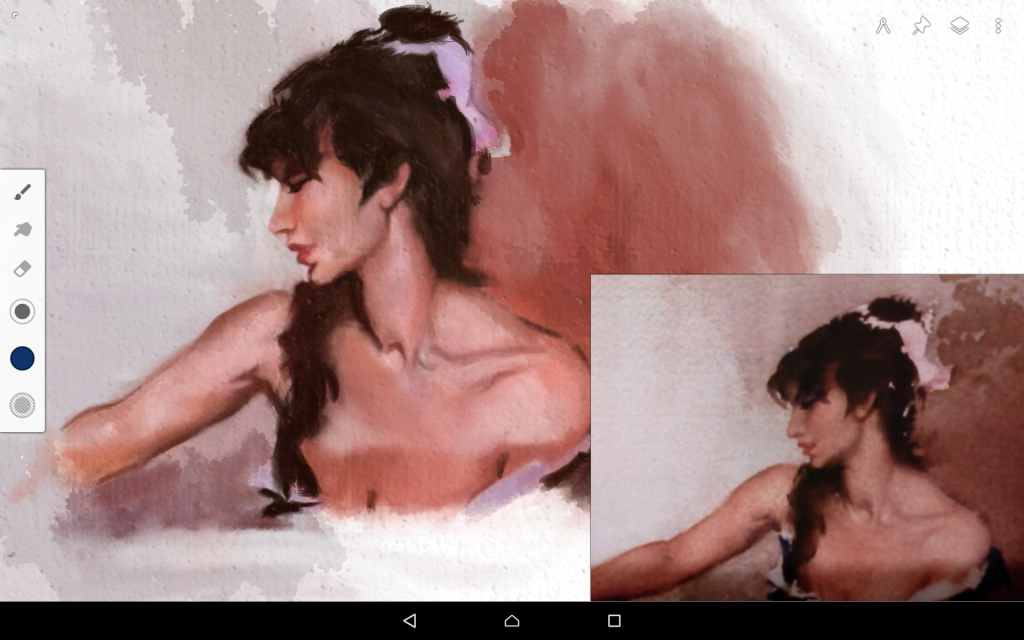

Finally, a detail from ‘Leaves From An Old Songbook’. I’ve attempted to copy a number of Flint’s figure paintings (with real paint) over the years and using the digital Wet-In-Wet brush gives a convincing emulation of the paint effects and the painting experience.

Conclusions

Over the years, I’ve attempted to copy a number of Flint’s paintings (with real paint); using Infinite Painter and the Wet-In-Wet brush gives a convincing emulation of both the paint effects and the painting experience. With a little practice, it’s possible to paint digitally much more quickly than with physical media. It’s an ideal outdoor painting medium: all you need is a tablet and a finger (I don’t use a stylus, so it really is digital painting).

For a painter used to working with traditional watercolour, there might be reservations about digital painting; it might be seen as an ‘artless’ pastime, heavily dependent on software and technology to create the result rather than the hands-on process of real painting. And up to a point this is true. The watercolour brushes of Infinite Painter, for example, are a black box to me; I can use them, tweak them, but I can’t hold them, dip them into a water jar and pick up paint from a palette with them. If the battery runs low on the tablet, I can’t paint.

I’ll probably always regard traditional watercolour painting as the ‘true’ medium. There is a pleasure in using the physical materials of painting that digital painting (even with graphics tablets and styli) can’t match. However, as learning tools, digital art packages have huge potential. They are certainly worth a try.

If you would like to watch the videos which accompany this post, click here.